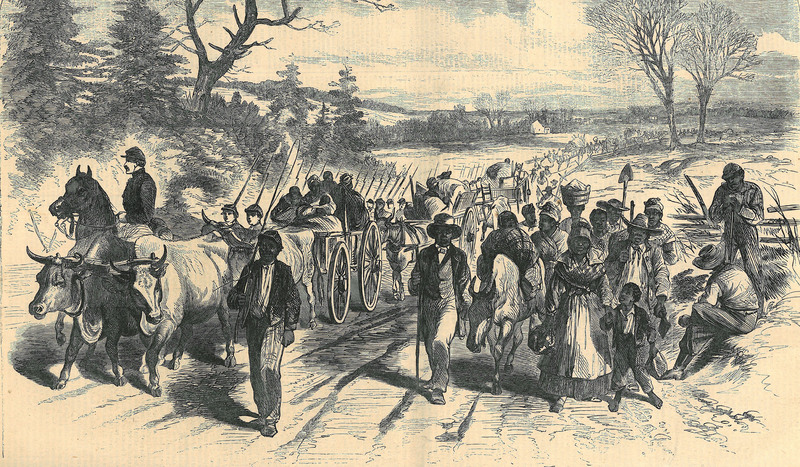

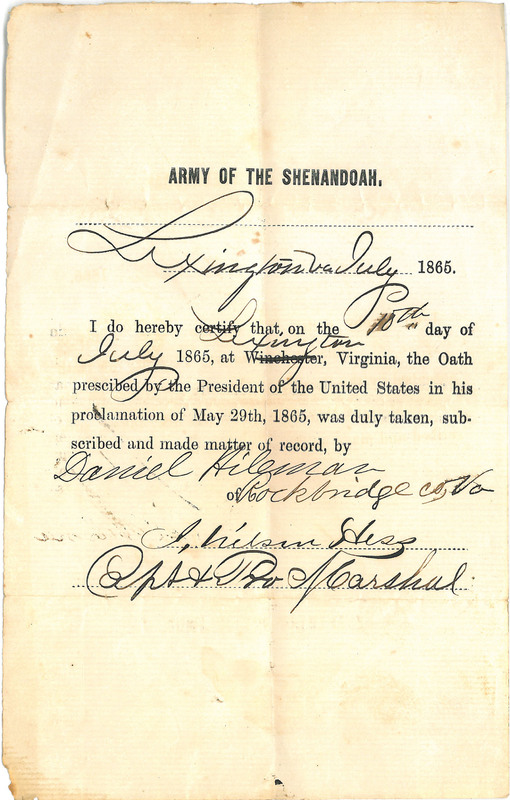

Defeat left Brownsburg in despair yet as always faithful and resigned to what its Presbyterian inhabitants interpreted as God’s will. “How many homes are devastated all over our land!”, Harriet Morrison wrote sadly from Bellevue. Six weeks after Lee’s surrender, her father commented: “The Yankees are now in Staunton and passed through Brownsburg to Lexington a few days since[,] then have since returned through Fairfield to Staunton. Many of the negroes have gone and more are dayly [sic] going. . . . [Illegible] Cousin Adam Brown’s have gone. As yet ours have remained. . . . We are constantly fearing incursion and interruption from the Yankees, but as yet we have been watched over by one who has all power in Heaven and on earth. Truly it is a gloomy time.”

Starting Over

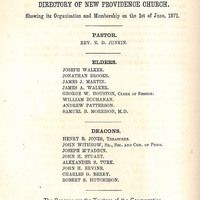

On the other hand, Henry Boswell Jones did not even notice the end of the war in his diary. One must read between the lines for any hints of Appomattox. On April 14, he wrote, “My son John came home a paroled prisoner,” and on May 1, “James Willson was buried today.” But before, between, and after these brief entries, Jones recorded the usual prosaic events, relating that he “plowed,” “planted sorgum” and “clipped sheep,” and that at New Providence on Sunday “a new Sabbath School was opened and Reverend [Ebenezer D.] Junkin gave the sermon.” Like many Brownsburg farmers, Jones, who had always performed most farm labor himself, was able to hire a few former enslaved individuals and continued to work his land successfully.

Some farms may have been lost in the immediate years after the war due to debt plus emancipation and other losses of invested capital, but no evidence of widespread hardship or social or economic upheaval in Brownsburg has surfaced.

Harriet Morrison, who never married, operated the Bellevue Home School after her father’s death in 1870 until shortly before she sold the farm in 1883. Her brother Sam practiced medicine in Brownsburg and Rockbridge Baths, eventually buying the bath house and hotel in the latter place. Jones farmed White Hall with his sons until his death in 1882.

A significant number of former slaves remained in and about the village. Black membership at New Providence persisted for decades after the war, although numbers gradually dwindled after freedmen organized the Asbury Methodist Church in 1869, apparently preferring separation and independence to rigid Calvinism and the deference expected of them in the predominantly white church.

The Walkers Creek School Board established a school for Black people in Brownsburg in 1870. It appears that few if any African-Americans were able to acquire their own farms, instead working in the village or in the homes and on the lands of whites. For Brownsburg as for the rest of the South, things would never be the same, nor would they be perfect; but people adjusted, and life went on.