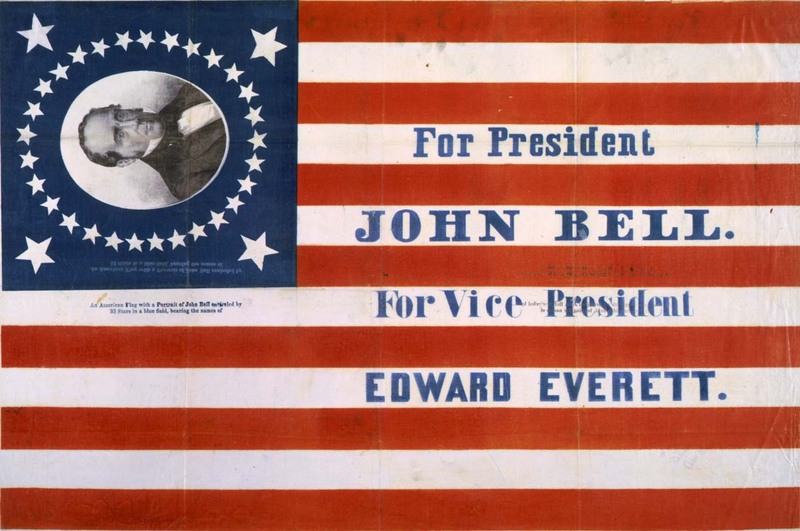

In one important way, however, Brownsburg residents departed from the Scotch-Irish norm. The Scotch-Irish were reputedly hot-headed and bellicose. But as disputes over whether America’s western territories should be open or closed to slavery fanned the flames of sectional passion to unprecedented levels in the 1850s, Rockbridge County generally and Brownsburg in particular remained calm. In the 1860 presidential campaign, Brownsburg rallied around the candidacy of John Bell, nominee of the new Constitutional Union Party in the four-man race. The party’s formation reflected anxiety about sectionalism and disunion; it put aside the vexing question of slavery in the territories, a matter on which North and South seemed perpetually unable to agree, and pledged fealty to the Constitution, the Union, and the law of the land, however the courts might interpret the Constitution and whatever the law of the land might be. Bell carried Virginia and every voting district in Rockbridge County, but his percentage in Brownsburg (80.6) was the highest among the county’s twelve precincts.

The Secession Crisis

Only eight of Brownsburg’s 227 votes were cast for John C. Breckinridge, nominee of the States Rights Democratic Party and advocate of federal protection for slavery in the territories—the smallest precinct total for Breckinridge recorded in the county. At the other extreme, Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln, running on a platform of exclusion of slavery from the territories, received no votes at all in Brownsburg and only one in Rockbridge.

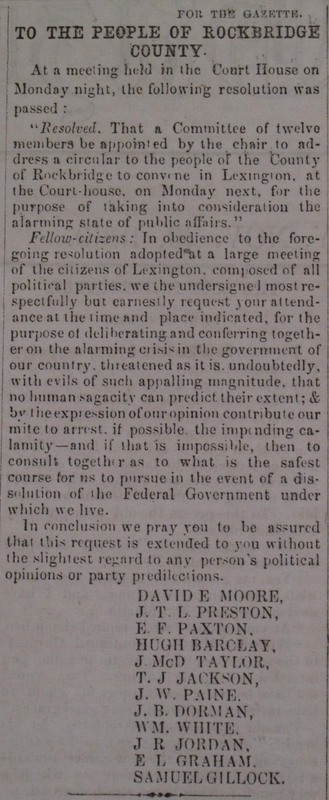

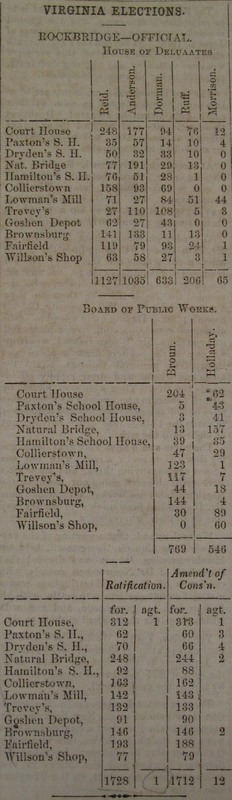

In the wake of Lincoln’s election, Brownsburg remained moderate; its citizens became what historians call “conditional Unionists” in the secession crisis. A town meeting on December 29 produced a resolution proclaiming loyalty to the Union and declaring secession acceptable only as a last resort should the incoming Republican administration violate the Constitution. In January, a national day of prayer and fasting over the crisis proclaimed by President James Buchanan was extended in Brownsburg to a week. Later in the month the state legislature voted to hold a special convention to consider the question of secession, as other slave states had done or were doing. Once again Brownsburg voters endorsed moderation and compromise. When votes for convention delegates were cast February 4, Rockbridge’s pro-Union candidates James Dorman and Samuel McDowell Moore combined to win 460 votes in the Brownsburg precinct to 3 for secession-leaning Judge John Brockenbrough and none for strong secessionist C. C. Baldwin. The Unionist candidates carried every voting district in the county (Unionists won a solid majority across the Commonwealth as well), but nowhere in Rockbridge was the tally as lopsided as in Brownsburg.

But again, Dorman and Moore, like most delegates elected statewide, were conditional Unionists. They believed that the incoming Lincoln administration, as the President-elect had declared, accepted the permanence of slavery in states where it lawfully existed, and that Lincoln would respect the right of slave states in the Deep South to leave the Union. Virginia Unionists were pro-slavery and pro-Union, and they were unconvinced that what New York Senator William Seward had called an “irrepressible conflict” between North and South existed. Irrepressible? Not if they could help it. Yet as Lexington’s Unionist lawyer James D. Davidson had presciently said, Virginia “will never bear coercion” of other states now proclaiming themselves Confederate. Most Virginians doubted the need for and wisdom of secession, not the right.

Unionist sentiment in Rockbridge began to erode after Lincoln’s inaugural address on March 4, in which he disputed secession’s legitimacy. Still, Virginia’s convention delegates defeated a secession ordinance 88-55 when it came to a vote a month later, with Moore and Dorman voting nay.

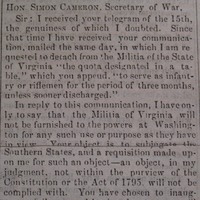

Lincoln’s call for states to furnish troops to suppress the “rebellion” after Confederates fired on Fort Sumter when U.S. troops, under orders from the President, refused to evacuate it changed everything in Brownsburg, in Rockbridge, and in Virginia (and in three more slave states of the Upper South, though not in four others, contrary to Confederate hopes). On April 17, 1861, a new secession ordinance passed the convention 88-45, with Dorman now favoring it and Moore initially opposing but then changing his vote. The legislature had made Virginia’s convention results subject to ratification by the voters, and on May 23 Brownsburg citizens endorsed secession unanimously. The tally countywide was 1,728 to one.

* All newspaper graphics from the Lexington Gazette