Hunter’s troops would go on to Lexington, where they burned selected houses and VMI and sacked Washington College before continuing their raid. Ironically, their delay in order to punish Lexingtonians for their perceived sins enabled Confederates to shore up defenses in preparation for what would be a decisive defeat of Hunter on June 17-18 at the Battle of Lynchburg, sending his army in retreat to West Virginia. One can only imagine the relief of Brownsburg’s white inhabitants when the divisions of Crook and Averell left. “They have done us much injury.” Henry Boswell Jones wrote in his diary. “Lord have mercy upon us and them.” For some of the slaves, however, the perspective on the Federal troops must have been different. The war did not begin as a struggle for freedom, but it had evolved into one. The appearance of U. S. soldiers had offered an opportunity for liberation, and when the soldiers departed some of the slaves probably went with them. Others remained, perhaps unsure about exchanging the only world they had known for a future less certain, perhaps influenced by the loyalty and affection that paternalism sometimes promoted notwithstanding the inequality inherent in it.

Hunter's Raid

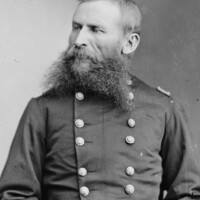

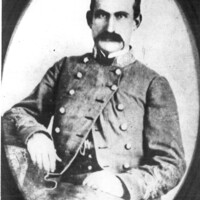

Until June 1864. A week after an embarrassing defeat at New Market on May 15, 1864, in which VMI cadets had played a key role, the U. S. War Department replaced General Franz Sigel with David O. Hunter and ordered the latter south to Staunton and Lynchburg, cities heretofore safely behind Confederate lines and important for their railroads, industries, and hospitals. Confederate troops in the Valley were few, and fewer still following the Battle of Piedmont on June 5, where General Hunter defeated a much smaller Confederate force under William E. (“Grumble”) Jones. Reinforced by cavalry commanded by William E. Averell and additional infantry under George Crook, Hunter left Staunton on June 10, splitting his forces to advance on Lynchburg by different routes. Crook and Averell followed the Middlebrook-Brownsburg Turnpike, skirmishing repeatedly with General John McCausland’s Confederate cavalry, strong enough to harass and delay the invaders but not to challenge them in a stand-up battle. When McCausland fell back to Lexington, the Federals bivouacked around Brownsburg, Averell at Bellevue and Crook nearer the village.

That evening and the next morning, June 10 and 11, Brownsburg and surrounding farms learned something of war firsthand. The raiders took horses and other livestock from the fields and plundered smoke houses, spring houses, barns, corn cribs, and other outbuildings; whether homes were entered is unclear. Losses would have been greater had residents not hidden many items upon learning of the approach of the enemy.

“Black Dave” Hunter would be reviled by generations of Virginians for the ashes he left elsewhere in the Valley, but no buildings in Brownsburg were burned nor was any resident physically injured. Condemned prisoner David Creigh, brought by the Federals to Rockbridge in chains, was less fortunate. Hanged at Bellevue before Averell’s troopers broke camp on the morning of June 11, the hapless Creigh would be transfigured through his tragic death into “The Greenbrier Martyr.”